Introduction To Machine Learning : Linear Regression

Introduction

In this post we are going to talk about one of the foundational techniques in Machine Learning, Linear Regression. Linear Regression is used when we want to fit a line to the data. The term regression refers to the fact that we are predicting continuous values like prices, amounts, etc. rather than discrete values such as categories, types, etc. We are going to look at some theory underlying the algorithm, get some data and code our algorithm!

Let us get the first thing out of the way, i.e., getting the data. We are going to code the algorithm as we go. So, fire up a text editor, and let’s get started!

We are going to learn about the basics of linear regression while working on the Boston Housing Dataset. This dataset is small enough to not cause any computational slowdowns but is big enough to help us get started. It comes pre-installed with the sklearn package that we downloaded earlier. So, now we have to import the dataset. We do this as follows:

import sklearn.datasets

boston_data = sklearn.datasets.load_boston()

Let us talk about some basics. First of all, Machine Learning, as we talked about, involves learning from data. More precisely, it involves generalizing from data. This means predicting values of previously unseen data, or data that we did not use when training the algorithm. That data is divided into two parts: Train Data and Test Data.

As the names suggests, when we train our algorithm, or when the algorithm is ‘learning’, we use the Train Data. Then, to test how well the algorithm did on the data, we give it new, or unseen data. That is the test data.

Some last bit of terminology, the data itself, regardless of whether it is Train or Test Data, is divided into two parts again: Features and Labels. Consider an example: We are trying to predict the amount of some drug required for a particular disease.

We have 500 samples, each from a different patient. In this case, each sample is called an ‘instance’. For each instance, let us assume we are using the three following variables to predict the amount:

1. Age of the Patient

2. Height of the Patient

3. Weight of the Patient

In this case, the Age, Height and Weight are called the ‘Features’, and the amount of drug that we are trying to predict is called ‘Label’.

What is Linear Regression?

Basically, Linear Regression, as the name suggests, involves linear equations, or lines. Regression refers to one of the two (of a few others) approaches to machine learning. Regression involves predicting continuous values, such as salary, prices, etc. A prediction in a Linear Regression model is given by \(y\) , where \(y = {w^T}x + b\). We will see the exact meanings of these terms below.

This is the basic terminology we need for now.

Linear Regression on the Boston Housing Data

Let us extract the Features and Labels from the Boston Dataset now. We do it with the following code, along with explanations below it:

features = boston_data['data']

labels = boston_data['target']

train_features = features[:400]

train_labels = labels[:400]

test_features = features[400:]

test_labels = labels[400:]

boston_data is a dictionary that can be indexed with keys and values just as we have seen in previous tutorials. The key ‘data’ gets the actual data, as a numpy array. The key ‘target’ gets the labels.

The next four lines perform an operation known as ‘slicing’. This is similar to what the name suggests, it slices an array from the starting point to the ending point.

So, the code features[:400] starts from instance 0 and goes upto but not including instance 400. Similar is the case with labels. For test data, we start with instance 400 and go upto the end. Notice how omitting (not entering any number) the start automatically assumes the beginning on the array, whereas omitting the end assumes the end of the array.

The process we just did above was a small part of what is known as Data Processing. Now, we talk about the actual algorithm below. In machine learning, to ‘learn’, we need to look at how wrong we are. To do that mathematically, we define an error function. Let us assume we have N samples or N instances (eg: N patients, say N = 100).

If we let \(y_n\) denote our answer, or ‘prediction’, and \(t_n\) denote the true answer, which is available in the training data at training time, then let us call \(y_n - t_n\) the ‘error’. So that \((y_n - t_n)^2\) is the squared error. Where the subscript n denotes the n’th training sample, say n = 50. If we sum over all the N samples, starting from 1 and going upto N in the training data, we get the following formulation:

\[\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^N (y_n - t_n)^2\]This is called the Mean Squared Error, or MSE. This is one of many functions that gives us a sense of “How wrong we are”. And it is this sense, or more formally, this function that we must minimize.

Posing The Problem

As we saw above, the problem is to minimize how wrong we are. To do this on a computer, we pose a function, a mathematical mapping that takes an input and returns an output, and we aim to minimize it.

That function is:

\[\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=1}^N (y_n - t_n)^2\]The meaning of the individual symbols is given above. We said \(y_n\) is our prediction, but how do we generate it? This the core question answered differently by different machine learning algorithms. For our purposes in this post, we are going to do that by taking what is called the dot product between two vectors. We explain each of these below:

One vector would be the feature vector which would contain our features for one instance (or one sample in the dataset). For eg: in our patient example above, each vector x would be a 3 x 1 vector, i.e., 3 rows and 1 column, with each row representing one of the following: Age , Height and Weight. So the vector would look something like:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cc} Age\\ Height\\ Weight \end{array} \right]\]So if Age = 20, Height = 179 cm, and Weight = 75 kgs, then the vector will look like:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cc} 20\\ 179\\ 75 \end{array} \right]\]Since the boston housing data contains 13 features for each instances, each vector x will be a 13 x 1 vector. To see exactly what those 13 features are, see point 7. and then following 13 points in this link. The 14th point we have to predict.

The other vector is what is called the parameter vector or the weight vector. This consists of our ‘learned’ weights, that when we combine with the instance vector, we get a real-numbered value. Here is a simple example explaining a dot product:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cc} 1\\ 2\\ 3 \end{array} \right] * \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 4\\ 5\\ 6 \end{array} \right] = (1 * 4) + (2 * 5) + (3 * 6) = (4) + (10) + (18) = 14 + 18 = 32\]So, we see that a product simply multiplies the corresponding elements in two vectors, does this for all the elements in the two vectors, and finally adds them. Note how two vectors are inputs, and the output is a single number.

Here is a mathematical way to write the dot product with our two vectors, x and w, which represent the instance vector and the weight vector, respectively:

\[\sum_{n=1}^N x_n * w_n = {w^T}x = {x^T}w\]If we now combine all the samples into one big matrix, with each sample forming a row in the matrix, then we can write our prediction as \(Xw\) , where w is our parameter vector and X is the ‘data matrix’. Note that this is a matrix-vector product. So if X has dimensions N x 13, N samples, each having 13 features.

While if w has dimensions 13 x 1. One for each feature that it will learn from the dataset, then result \(y_n\) will be a N x 1 vector. Each row (or term, because of 1 column, each row has a single term), will contain our prediction for that particular instance from the dataset.

Using this notation, we can finally write the error function in a slightly different form as :

\[(Xw - t)^2 = (Xw - t)^T (Xw - t)\]Here the vector t indicates that we have combined all the labels of instances into one vector. Also, X contains all instances, with each row in the dataset forming a row in X. We have explained above that Xw is a matrix-vector product and returns an N x 1 vector.

Since t also contains the labels (which are just numbers representing the house price) for all the instances, it is also N x 1. Thus, we can perform subtraction. Note that vector subtraction is element-wise, as shown below:

\[\left[ \begin{array}{cc} 10\\ 20\\ 30 \end{array} \right] - \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 2\\ 5\\ 6 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 10 - 2\\ 20 - 5\\ 30 - 6 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 8\\ 15\\ 24 \end{array} \right]\]Solving the Problem

With this, we can expand the error function we just wrote above as follows:

\[(Xw - t)^2 = (Xw - t)^T (Xw - t) = ({w^T}{X^T} - {t^T})(Xw - t)\]Note that here, \(A^T\) denotes the transpose of a matrix A. We have used the property: \({(AB)}^T = {B^T}{A^T}\).

Now, we can write the above as:

\[({w^T}{X^T} - {t^T})(Xw - t) = {w^T}{X^T}{Xw} - {w^T}{X^T}t - {t^T}{Xw} + {t^T}t\]This is the error function which we can write as:

\[E(w) = {w^T}{X^T}{Xw} - {w^T}{X^T}t - {t^T}{Xw} + {t^T}t\]This is a function of w, the weight vector, since X is the matrix of train features and t is the vector of train labels, both of which are fixed. We now need to minimize this function, to do so, we need the partial derivative of the function with respect to the weight vector.

If you do not know what a partial derivative is, here is a great introduction to the topic.

We look at the specifics of multivariable differential calculus we need and then derive an algorithm that we can finally implement in code:

\[\frac{\partial E}{\partial w} = \frac{\partial ({w^T}{X^T}{Xw} - {w^T}{X^T}t - {t^T}{Xw} + {t^T}t)}{\partial w}\]The quantity we are interested is the one on the right above:

\[\frac{\partial ({w^T}{X^T}{Xw} - {w^T}{X^T}t - {t^T}{Xw} + {t^T}t)}{\partial w}\]Which, on taking the partial derivatives gives:

\[2{X^T}{Xw} - {X^T}t - {t^T}{X} = 2{X^T}{Xw} - 2{X^T}t\]To minimize this quantity, we set it to zero, and get:

\[\frac{\partial E}{\partial w} = 2{X^T}{Xw} - 2{X^T}t = 0\]From this, we get:

\[2{X^T}{Xw} = 2{X^T}t\]Dividing both sides by 2, we get:

\[{X^T}{Xw} = {X^T}t\]Now, remember that for any matrix \(A\), \({A^{-1}}A = I\) where I is the Identity Matrix and \({A^{-1}}\) is the inverse of \(A\).

Multiplying both sides above on the left with \({({X^T}{X})^{-1}}\), we get:

\[w = {({X^T}{X})^{-1}}{X^T}t\]Thus, we have finally reached the weight vector we were looking for. We are now ready to implement this in code!

We can now make predictions using w, so that our predictions will be:

\[Xw = y\]Where y is an N x 1 vector, containing N predictions, each corresponding to an instance.

Implementing the algorithm in code

Let’s put the whole code at once here and then explain it bit by bit, remember that we have already done the data loading and proccessing parts. Here is the code:

import numpy as np

import sklearn.datasets

# OLS Linear Regression

def linear_regression(X, Y, X_, Y_):

# estimate for the weight vector W, can be found by minimizing (y - WB).T * (y - WB)

W = np.matmul(np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X.T, X)), np.matmul(X.T, Y))

predictions = []

# iterate over the test set

for entry in range(len(X_)):

# get prediction

pred = np.matmul(W.T, X_[entry])

predictions.append(pred)

predictions = np.array(predictions)

# compute MSE

error = np.sum(np.power(predictions - test_labels, 2)) / 2

return (W, error, predictions)

# load the dataset

boston_data = sklearn.datasets.load_boston()

features = boston_data['data']

labels = boston_data['target']

train_features = features[:400]

train_labels = labels[:400]

test_features = features[400:]

test_labels = labels[400:]

# fit the data

lr_pred = linear_regression(train_features, train_labels,

test_features, test_labels)

# view our predictions vs the actual targets

for j in range(len(test_labels)):

p = lr_pred[2][j]

t = test_labels[j]

We start by breaking down the code bit by bit. We first import the packages we need:

import numpy as np

import sklearn.datasets

Now, using these, we define a function called linear_regression, that contains our algorithm. This function takes as arguments the train features, train labels, test features and test labels. These are denoted by X, Y, X_ and Y_ respectively.

Now, we find the weight vector using the formula we derived above, here it is again:

\[w = {({X^T}{X})^{-1}}{X^T}t\]In code, here is the implementation:

W = np.matmul(np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X.T, X)), np.matmul(X.T, Y))

np.matmul(A, B) multiplies the two matrices A and B. np.linalg.inv(A) finds the inverse of the matrix A. In the above definition of W, we have just chained these commands together to find W quickly.

This one line was the core of our algorithm! Notice that this uses the train features and the train labels. We are now ready to make predictions on the instances present in the test features, grouped together in a matrix X_, and check our predictions against the true values Y_, the vector.

We do this as shown:

predictions = []

# iterate over the test set

for entry in range(len(X_)):

# get prediction

pred = np.matmul(W.T, X_[entry])

predictions.append(pred)

predictions = np.array(predictions)

Here, we create a list called predictions to store our predictions. Next, we go over the whole test set, looking at each instance on by one, denoted in our for loop by the name entry. Make sure you see that entry is an integer that goes from 0 upto and including len(X_) - 1. So that X_[entry] gets us an instance from the test set.

Next, we take the dot product between our weight vector and the instance from the test set and store that value in the variable pred. Then, we append that to the list predictions to store it for later comparing. We repeat this process for all the samples in the test set.

We finally convert predictions from a list to a numpy array. This is because we cannot do mathematical operations on lists, but we can do them on numpy arrays.

The final step is to calculate the error we made while predicting, we see this with the formula we had earlier:

\[\frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^N (y_n - t_n)^2\]Here it is in code:

error = np.sum(np.power(predictions - test_labels, 2)) / 2

Let us go from inside to the outside on the command, the innermost part finds the element-wise difference between our predictions and the true values, then it raises that vector (this will be a vector, remember, the difference is element-wise) to the power of 2.

Now, np.sum(v) adds up all the elements in the vector v and returns a single number, the sum of all the elements in the vector v. So the vector that was squared, now has all its elements added together and finally we divide this sum by 2 and store this in the variable error.

We finally return the weight vector W, the error variable and the predictions array from this function.

return (W, error, predictions)

Next we prepare our data, since we have already done this before, here is the code:

# load the dataset

boston_data = sklearn.datasets.load_boston()

features = boston_data['data']

labels = boston_data['target']

train_features = features[:400]

train_labels = labels[:400]

test_features = features[400:]

test_labels = labels[400:]

Now we can call our function as shown:

# fit the data

lr_pred = linear_regression(train_features, train_labels,

test_features, test_labels)

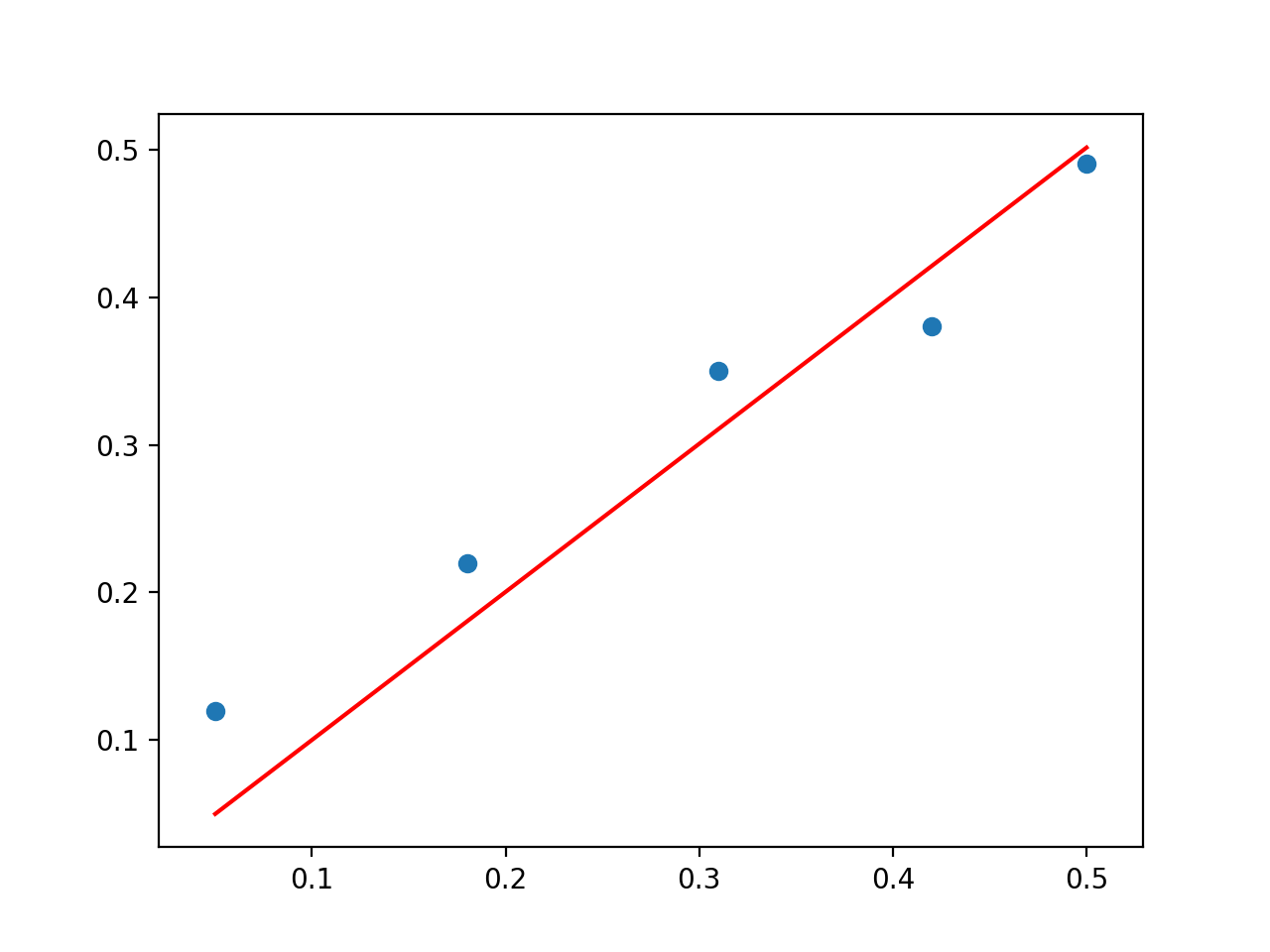

We would also like to visualize our results, so we would like to print our predictions against the true values. We do this as follows:

# view our predictions vs the actual targets

for j in range(len(test_labels)):

p = lr_pred[2][j]

t = test_labels[j]

print(p, t)

See how we use two indices to get our prediction and store it in the variable p. This is because the function linear_regression returns three values that we stored in the variable lr_pred. The last element of those three is our predictions array, which we get with index 2, because in python, indexing starts at 0. This means the first element is at index 0, second at 1 and the third at 2.

Then we get the true label and then we print the two values against each other in the same line.

Running the Code

Now, we run our code! Save the file in your text editor as filename.py . Remember the file extension .py is extremely important! It tells the computer that this is a python file. Open cmd, navigate to the directory where you saved the python file.

You can change directories in the cmd using the command cd and then using the directory name. So, to go into a directory called Programs, we would use the command cd Programs/.

Once you are in the directory where your python file is, type python filename.py and there you have it !

Go over the code and the math again if you feel you need to wrap your head around it. It can take some time if you are seeing this for the first time.

This completes this post. If you did this all in one stretch then give yourself a pat on the back!

Further places to read more are Wikipedia, also check out YouTube, and if you feel like diving deep, see the book : Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning by Bishop.

Thanks for Reading, I’ll see you next time!