A Python Primer : Programming Basics

Hello! In this post we are going to go over the parts of the Python Programming Language and of the software packages (which we installed last time) that will be most relevant to us. If you are interested in learning more of the language and the libraries, links will be provided at the end.

Let’s start! Fire up your text editor (or open cmd and type ‘python’), and follow along. We will cover variables, loops, functions, some basic data structures like lists, dictionaries and sets. We will also use basic functions of the numpy library and finally close with some basic plotting with matplotlib. All this will be extremely useful starting from the next post when we start working with actual biological data.

If you are working in cmd, then typing in python should give something similar to this:

tushar@home:~$ python

Python 3.6.5 (default, Apr 1 2018, 05:46:30)

[GCC 7.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

Ofcourse the exact output might differ, what’s important is you should see the prompt (the three ‘>’) at the end.

VARIABLES

A variable, as the name suggests, are objects that are dynamic rather than static. This means the value they store can be changed. A simple example is:

>>> x = 25

This simple example highlights one of the most important features of Python – simplicity and readability. This command stores the integer value 25 in x. To see this, type in:

>>> x

25

>>>

Simple addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and exponentiation (raising a number to some power) can be done as shown:

>>> y = x + 13

>>> x

25

>>> y

38

>>> y - x

13

>>> y + x

63

>>> y * x

950

>>> y / x

1.52

>>> y ** x # exponentiation, raising y to the power of x

3123128945369882154942078678703504621568

>>>

Equalities and Inequalities can be checked in very simple ways. Here is an example:

>>> x = 5

>>> x == 5 # check if is equal to 5, note how two equal signs are used. One equal sign denotes assignment

True

>>> x != 5 # check if x not equal to 5

False

>>> x > 5 # check if x greater than 5

False

>>> x < 5 # check if x less than 5

False

Comments in Python start with ‘#’, everything after this Python does not interpret as code and ignores it. This completes our requirements of Python variables. We next take a look at loops.

LOOPS

As the name name suggests, a loop is way of doing some operation repetitively until some condition is true, or for a fixed number of times, or even forever! There are 2 major types of loops, the ‘for loop’ and the ‘while loop’.

The ‘for’ Loop

We will first look at a for loop. A for loop does an operation some fixed number of times as specified by us and then once it has completed that step said number of times, it stops. In Python, a for loop behaves a little differently than some other languages and it can be used in a variety of ways. We will see 2 most common ways. An example is given below:

# a simple for loop

>>> counter = 10

>>> for c in range(counter):

... print(c)

...

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>>

The variable ‘c’ starts from the value 0 and goes upto (but not including) 9.

One thing to point out, range is a function that does something similar to the literal meaning of its name. range starts from a beginning variable (usually 0, but we can set it to anything we like, see example below) and goes upto (but not including) the value we give it (in our case 10). We will talk more about functions below.

# another simple for loop

>>> counter = 10

>>> for c in range(2, counter):

... print(c)

...

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>>

A for loop can also act in a reversed manner. That means, in our case, we could start from 10 and go down to 0. Here’s how:

>>> for c in range(counter, -1, -1):

... print(c)

...

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

>>>

Here, the first value is 10 (equal to our variable ‘counter’), the second value is stop value (equal to -1, because the loop goes upto but does not include the -1. As an exercise, see what happens if you put 0 instead of -1). The third value is the number by which we should decrease our current value of the variable ‘c’.

The ‘while’ loop

The ‘while’ loop is the other major type of loop that we use in programming. Similar to the ‘for’ loop, it runs until a condition is True rather than upto some fixed value. An example is shown below (read comments in the code!):

>>> age_till_adult = 18

>>> current_age = 5

>>> while current_age < age_till_adult: # the condition that checks whether to stop or keep going

... print('I am {} years old.'.format(current_age)) # see explanation below

... current_age = current_age + 1 # Important to increase the variable, otherwise the loop will run forever!

...

I am 5 years old.

I am 6 years old.

I am 7 years old.

I am 8 years old.

I am 9 years old.

I am 10 years old.

I am 11 years old.

I am 12 years old.

I am 13 years old.

I am 14 years old.

I am 15 years old.

I am 16 years old.

I am 17 years old.

>>>

The print function (we talk about functions below) above uses a type of ‘substitution’, in that the value takes the place of the ‘{}’. This substitution is done by the .format() part, which helps us in writing reusable print functions. If you have more than one the curly braces (as they are called), the order in which you pass the variables is the order in which they will appear in the string. An example is shown below:

>>> country_1 = 'Brazil'

>>> country_2 = 'Argentina'

>>> print("{} might win the 2018 FIFA World Cup. However, it's not looking good for {}".format(country_1, country_2))

Brazil might win the 2018 FIFA World Cup. However, it's not looking good for Argentina

>>>

Another thing to point out is the variable update. Instead of: current_age = current_age + 1, we can also use: current_age += 1 , this is easier to read, but a might take some getting used to. The same holds for subtraction, multiplication or division.

That does it for loops, next we talk about functions.

FUNCTIONS

A function is a utility in programming that allows us to reuse the same block of code. This might happen if you were to perform the same computation, but the input values kept of changing. For example: Logging some patient data, with each patient having different details or Performing some calculation that involves the same formula, but the inputs keep changing, etc. .

A function takes inputs (also called arguments) and returns outputs (also called return values).

Saying the same thing, but a little more formally, we can write: Function: Inputs -> Outputs. In Python, we need 3 components for creating a function:

1. The keyword def . This tells Python we intend to create a function.

2. The name of the function, followed by circular brackets ( ’()’ ), which contain the arguments.

3. The return value of the function.

After you have defined a function, you need to call it. This is done by typing the function name, then passing the arguments it takes within the circular braces.

Let’s put this all together and see an example of a function that prints a nice introduction for you given your first name and then call it.

>>> def introduction_generator(first_name): # define the function

... introduction = "Hi, my name is {} and I like football!".format(first_name)

... return introduction # return value

...

>>> name = 'Tushar'

>>> introduction_generator(name) # call the function

'Hi, my name is Tushar and I like football!'

>>>

Try changing the string introduction inside the function. Try changing the argument first_name and try passing different values.

As a last point, we can easily extend our function to have more than a single argument. An example follows below:

>>> def introduction_generator(first_name, last_name): # define the function

... introduction = "Hi, my name is {} {} and I like football!".format(first_name, last_name)

... return introduction # return value

...

>>> first_name = 'Tushar'

>>> last_name = 'Chaturvedi'

>>> introduction_generator(first_name, last_name) # call the function

'Hi, my name is Tushar Chaturvedi and I like football!' # :)

>>>

This completes our discussion of functions. One last topic on the Python Basics remains, Data Structures.

DATA STRUCTURES

LISTS

A list is a generalization of a variable. Where a variable stores a single value, a list can store multiple values. Here is an example:

>>> ages = [18, 20, 40, 50, 32, 15]

>>> ages

[18, 20, 40, 50, 32, 15]

>>>

We can lists of other data types such as strings too.

>>> names = ['python', 'perl', 'c++', 'julia']

>>> names

['python', 'perl', 'c++', 'julia']

>>>

Moreover, we can even mix these data types! Here is another example:

>>> names_and_nums = ['python', 'perl', 18, 'c++', 20, 10]

>>> names_and_nums

['python', 'perl', 18, 'c++', 20, 10]

>>>

We can thus mix different data types in a list, in any order.

Let us iterate (look at each element one by one) over a list and print its contents.

>>> for entry in names_and_ages:

... print(entry)

...

python

perl

18

c++

20

10

>>>

Another important function related to lists is append . As the name suggests, using this function we can add new values to the list. Here is an example:

>>> number_inputs = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

>>> number_inputs.append(11)

>>> number_inputs

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

>>>

An important feature of lists is what is called list comprehension. It provides a quick way to create lists. This will be very useful to us tomorrow. Here is an example:

>>> x = [j ** 2 for j in range(10)] # iterate in the range and square each number and store it

>>> x

[0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100]

>>>

We can do much more! For links, see the end of the post.

DICTIONARIES

As the name would strike a meaning, that very meaning is what a dictionary in Python does. It contains keys, each of which corresponds to a value, much like in a real dictionary where the keys are the words and the values their meanings.

Here is an example:

>>> age_dictionary = {'person1':18, 'person2':20, 'person3':22, 'person4':2}

>>> age_dictionary

{'person': 18, 'person2': 20, 'person3': 22, 'person4': 2}

>>>

This is a string where names have ages as values. The : (colon) indicates a separation. The entries to the left are keys, to the right are values. Each key-value pair is separated by commas.

To access a value (analogous to finding a meaning), we do as shown:

>>> age_dictionary['person']

18

>>>

also

>>> age_dictionary['person4']

2

>>>

We can even change the value associated with a key. Here’s how:

>>> age_dictionary['person4'] = 200

>>> age_dictionary['person4']

200

person4 is really old !

Sets

A set is a data structure that does not contain any duplicates. Here is an example:

>>> x = [1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,6] # we first declare a list

>>> x

[1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6] # It contains duplicates

>>> y = set(x) # we call the set function, passing x as the argument. It returns the set y.

>>> y

{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} # Voila! y does not contain any duplicates.

For our purposes, that’s all there is to sets really! That completes our discussion of Python basics. We will now talk about some basics we need for numpy and matplotlib. Consider taking a break! :)

NUMPY BASICS

Numpy is a software package for Python that helps with Mathematics. It is a huge library that has many other software packages built on top of it. Here, we will see only what amounts to a drop in the ocean that numpy is ! We will see basic matrix operations and vector operations. But for those of you who want to know what a matrix and a vector is, we will cover them in the next post where we start with Machine Learning. In the meantime, here is a great video series on them Linear Algebra Tutorials.

Creating a vector is very simple with numpy. But first we must tell Python we intend to use it. In Python, we do this by typing:

>>> import numpy

>>>

In Numpy, we create vectors and matrices using the array function (technically, it is a method, but right now this is not relevant to us). We usually do this by passing a list to the array function. An example is shown below:

>>> number_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> X = numpy.array(number_list)

>>> X

array([1, 2, 3, 4])

This creates an array (a vector) for us. To verify this is a vector, we check to see this really is a vector, we see the shape of X. We do this by:

>>> X.shape

(4,)

We see X has 4 rows and 1 column (though the entry after the comma is empty, so that this is a row rather than a row vector, we show below how to make the fact that this is a row vector explicit). The shape was (4,). We would like to be very precise, to have the shape be (4,1), indicating 4 rows and 1 column. We can do this by:

>>> X = X.reshape(4, 1)

>>> X

array([[1],

[2],

[3],

[4]])

>>>

We assign to X its updated (reshaped) value. Now when we check to see the shape we see:

>>> X.shape

(4, 1)

>>>

There we go!

The extension to making matrices is similar. The difference is when using reshape, we assign row and column numbers directly. In our current example, creating a matrix would look like:

>>> import numpy

>>> number_list = [1,2,3,4]

>>> X = numpy.array(number_list)

>>> X = X.reshape(2, 2)

>>> X

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4]])

>>>

Checking to see the shape, we have :

>>> X.shape

(2, 2)

>>>

There we have it !

We have to talk about 2 more simple operations, Matrix Multiplication and Matrix Transposing. If you do not know what these are, we will cover these later. In the meantime here are links to good videos explaining them:

Matrix Multiplication -> Matrix Multiplication

Matrix Transposing -> Matrix Transposing

In our example, we can do Matrix Transposing as follows:

>>> Y = numpy.transpose(X)

>>> Y

array([[1, 3],

[2, 4]])

>>>

For Matrix Multiplication, this is how we would do it:

Y = X + 1 # this operation is element-wise, meaning that it adds 1 to each element of X, and the new matrix is assigned to the variable Y

>>> Z = numpy.matmul(X, Y)

>>> Z

array([[10, 13],

[22, 29]])

>>>

That completes Numpy Basics. The last topic that remains is Matplotlib, with which we can plot graphs and figures.

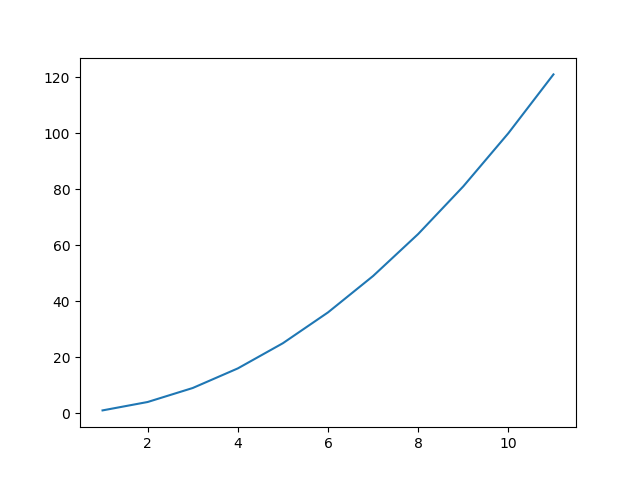

MATPLOTLIB

We require matplotlib for the purposes of monitoring the progress of metrics such as accuracy and error while we train our algorithms. As a result, we require for the most part, a single function from the library. Let us create a function that squares numbers and plot it, with inputs on x-axis and the function values on the y-axis. This will use everything we have read so far, so take your time when you read this code. Be sure to read the comments! Here is the example :

>>> import numpy # import numpy

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot # import plotting function

>>> def square_function(x): # define our squaring function

return x ** 2

>>> number_inputs # define our inputs

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

>>> number_inputs = numpy.array(number_inputs) # convert them to a vector, so we can do maths on it. Skip this step if want to see why this is important.

>>> number_outputs = square_function(number_inputs) # apply squaring function to vector element-wise

>>> plt.plot(number_inputs, number_outputs) # plot inputs on x-axis, outputs on y-axis

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D object at 0x000000C291B64CF8>]

>>> plt.show() # show the graph

>>>

The output should look like this:

And we did it! These are all the Python Programming basics we need to start implementing our Machine Learning algorithms. From the next post, we will dive into the details and the mathematics of the algorithms, and all the relevant Maths will be explained there! Give yourself a pat on the back if you honestly did the whole tutorial!

As said above, links to resources that cover Python in much more depth are here:

Sentdex : Python Programming Basics

Codecademy: Awesome For Learning Practical Programming

Official Python 3 Docs: From The People Who Created The Language

Wish you good luck and Thanks for Reading, See you next time!